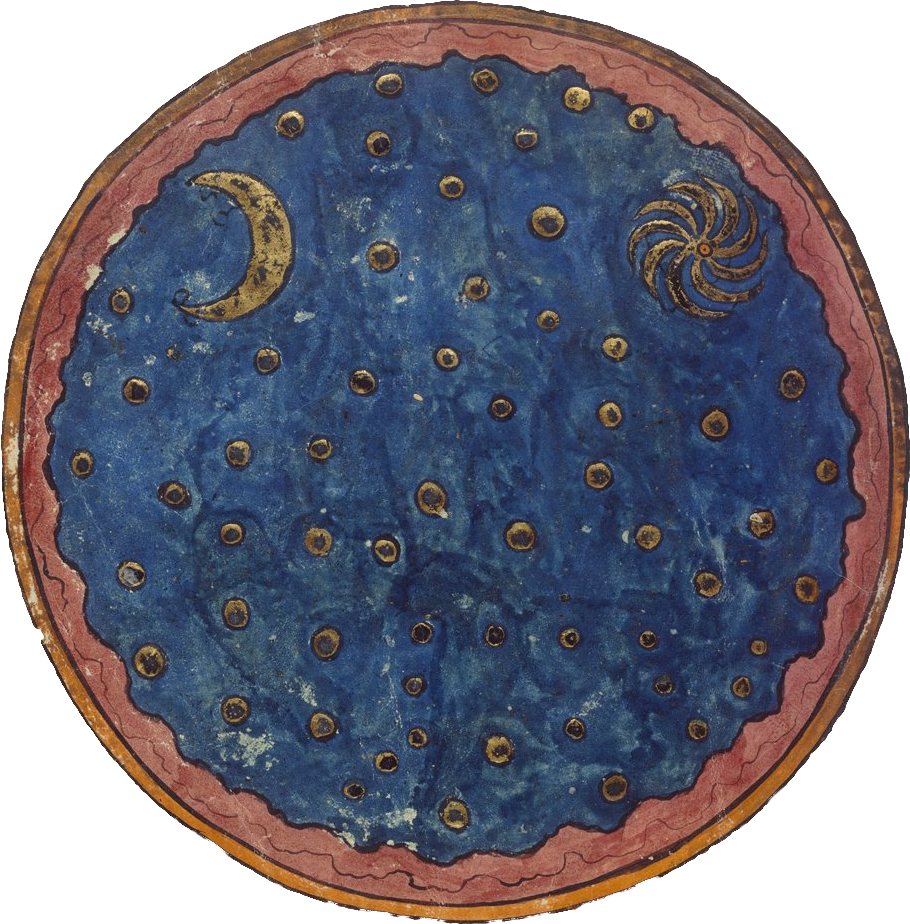

You ask, my Lesbia, how many of your kisses would be enough and more than enough for me? As many as the Libyan grains of sand that lie at silphium bearing Cyrene between the oracle of stormy Jove and the sacred tomb of old Battus; or as many as the stars who, when night is silent, see the secret loves of men. That many kisses would be enough and more than enough for loved crazed Catullus to kiss you, kisses which neither the curious can count nor an evil tongue bewitch. -- Catullus

I don't mean an atom like on the periodic table, which is really a complicated enough thing of its own "made of" electrons, protons, neutrons, and so forth. I mean, an actual atom. The word in Ancient Greek means something indivisible. Sometimes "atomism" is characterized as the belief that the world is made of tiny little hard impenetrable pebbles whizzing around in empty space, perhaps, according to Lucretius, swerving from time to time in a pique of will. But in a literal sense, atomism is the idea that the world is in some sense composed of indivisibles. We can divide something up, but at some point we won't be able to divide any longer. And what's left are the atoms.

One could interpret this "materialistically" that what's left is tiny little bits of "matter", perhaps differently shaped, perhaps of different substances, that can fit into each other in different ways. But "idealistically", we could interpret this as a reflection on the fact that when we analyze an idea, what we do is we reduce it down to a bunch of basic concepts fitted together into a jigsaw; and the most basic concepts have to be taken for granted, atomically. Of course, an idea can be interpreted in many ways, expressed in different ways as a complex of perhaps different basic concepts. So that from one point of view, a concept can be resolved into these atoms; whereas from another point of view, the concept can be resolved into some other notion of atoms. We prove our understanding to each other by demonstrating how we can reduce some shared concept into some agreed upon atoms. And arguably, what we mean by "understanding" is the ability to apprehend what something "is made of" immediately upon recognizing it.

It's worth observing that when the materialist wants to have their atoms be tiny little "physical" cubes or octahedra, knocking around, naturally selecting, in actual practice, what they really need to do is plausibly reduce all their concepts down into a single set of basic atomic concepts, which correspond exactly to the ideas of "the tiny hard impenetrable sphere," "the tiny little pyramid," out in the real world. When put this way, it actually seems rather extravagant. While it is "obvious" in some sense that ideas can be analyzed into atomic ideas, it would be really quite something if all concepts could be reduced to jigsaws made of exactly the same ideas. It would mean all those different ways of analyzing concepts were really worthless: after all, why not just use the universal ideas, the universal atoms?

The materialist could respond: The real world is made up of one set of atoms; it's only in the mind that we can analyze concepts into seemingly different inequivalent atomic schemes, leading to the disagreement and confusion. The response at this juncture can only be that if you're willing to consider that, why not consider the case where, it's only in the mind that all concepts can be reduced down to a single set of ur-concepts (your own!), whereas in the real world, real things can be reduced down to ur-concepts in different inequivalent ways.

The only way to proceed is to actually try to do it: we have to try to divide the world and our concepts into universal atoms and see what happens.