We find already in Plato the doctrine that if anything is beautiful in its kind, this is not because of its color or shape, but because it participates (Greek) in "that," viz. the absolute, Beauty, which is a presence (G) to it and with which it has something in common (G). So also creatures, while they are alive, "participate" in immortality. So that even an imperfect likeness (as all must be) "participates" in that which it resembles. These propositions are combined in the words "The being of all things is derived from the Divine Beauty." In the language of exemplarism, that Beauty is "the single form that is the form of very different things." In this sense every "form" is protean, in that it can enter into innumerable natures.

Some notion of the manner in which a form, or idea, can be said to be in a representation of it may be had if we consider a straight line: we cannot say truly that the straight line itself "is" the shortest distance between two points, but only that it is a picture, imitation or expression of that shortest distance; yet it is evident that the line coincides with the shortest distance between its extremities, and that by this presence the line "participates" in its referent. Even if we think of space as curved, and the shortest distance therefore actually an arc, the straight line, a reality in the field of plane geometry, is still an adequate symbol of its idea, which it need not resemble, but must express. Symbols are projections of their referents, which are in them in the same sense that our three dimensional face is reflected in the plane mirror.

-- Ananda K. Coomaraswamy, "Imitation, Expression, and Participation"One thing that's often underemphasized in writing about physics is how important representations are, and how most of the technical details are actually about proving things like: X really represents what I say it does. Because the fact is that pretty much anything can represent anything else, but if you choose your representation at random it's probably going to suck: which I mean in a technical sense: to use it, it'll require a lot of book-keeping and bending over backwards to keep track of things. E.g., I can represent a library as a bunch of 0's and 1's, but that will make it difficult of me to read. Words in contrast are good for humans in this respect.

Ideally, the goal is to find representations of things that make as few unnecessary distinctions as possible so that anything you can naturally do to the representation has a unique meaning in terms of the thing it represents. And we have to understand "representation" w/r/t to human beings and our minds/bodies.

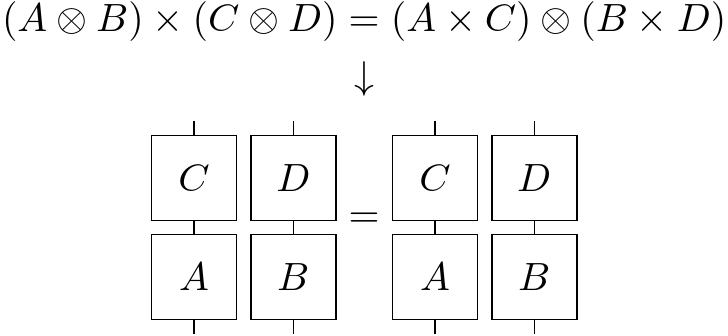

An example:

Above we have a line of symbols where some kind of "algebra" is going on. We have a bunch of symbols A B C and D. And we have two things we can do to them: the "O with a cross" (called the tensor product) and the "cross without an O" (called multiplication). And according to the rules governing these two actions, the first line is a true statement, an "equation": A tensor B times C tensor D is just the same as taking A times C and tensoring it to B times D.

But maybe using "algebra" is actually sort of dumb. For example, below it is a better representation, which lives in 2D, on the full paper, not just along a 1 dimensional row of symbols/single line of text. In this representation, with wires and boxes, the former equation is actually a tautology--it's literally just a thing = itself: not even worth bringing up! It doesn't even have to be proven since the representation itself doesn't make the unnecessary distinction whose symptom is actually the ability to write a so-called "equation" at all, which might require proof: a sequence of allowed actions that bring the "left" into the same form as the "right". To wit, the essence of the analogy is: we represent A, B, C, and D as boxes with wires coming in and out of them. And "tensor" means put side to side. And "multiply" means put atop/below.

To reiterate, when we represented this "truth" with a linear sequence of symbols and some rules for rearranging those symbols, we could write down an "equation"--but this was only possible because there was a redundancy in the symbolism: here's two statements that actually "mean" the same thing, they're equal, even though there are two ways we can write them. In contrast, when we use a "planar diagram" instead, we don't even need to "prove" that the equation is "true": it's just literally obvious. And that makes it a better representation.

Now it turns out that if we define A, B, C, and D to be matrices/grids of numbers, and take "O with a cross" to mean combine the two matrices in a fancy way we call the tensor product, and "cross without an O" to mean matrix multiplication, another way of combining matrices, then it is a fact that our "equation"/tautology is also true of those matrices. So that whatever else is true about these matrices, each full of possibly gazillions of numbers which are a pain in the ass to keep track of, you won't go wrong representing them as boxes with wires.

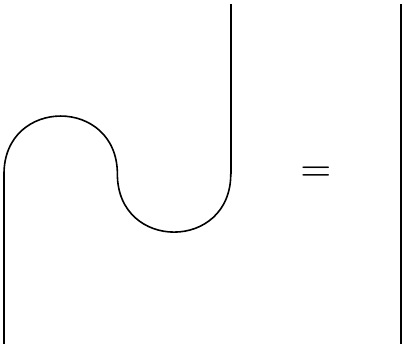

Now it turns out another equation which one can write out in the algebra, but also with the diagrams, and also with the matrices is this one:

And it says that you can "yank" a string straight and it doesn't change the meaning at all. So a planar diagram per se is imperfect too-- by statically depicting the situation in a single image, it make an "unnecessary" distinction.

And so, it turns out that literally a piece of string is the best representation of how these symbols/boxes/matrices can be wired together. Anything you can do to the string you can also do to the matrices. So if you are playing around with the string, you're also playing around with the matrices, and it's like: the guardrails are up: you literally cannot fail to make a true statement about the matrices.

At last then: we interpret each wire to represent a "quantum system," and each matrix to represent the "time evolution of that quantum system" (we have to require a few things of our matrices, certain symmetries, for this part to work: so that matrices themselves are "imperfect representations" in the same sense as the symbolic algebra before). And a "cup" aka a U shape represents: two maximally entangled quantum systems side by side in space, and a "cap" represents: a filter which tests whether two quantum systems are in the maximally entangled state (which the systems may pass with a certain probability). Whatever this means, the important point is this: now by playing around with my boxes connected by pieces of literal string, doing anything I can do to them in real life, I cannot fail to make true statements about a bunch of evolving possibly entangled quantum systems being prepared, processed, and measured in the lab. (And by the way, this doesn't in itself have anything to do with "string theory".)

So that indeed, the matrices and the literal physical systems themselves "participate in" stringiness. They are as much connected by strings as anything else connected by strings. If by string you mean, whatever it is all strings have in common, whatever it is that is so obvious about strings that otherwise you'd pass over in silence unless you were representing them in some other language which makes distinctions irrelevant to STRINGINESS itself. And we find ourselves in a kind of weird transcendent position, doing both--both participating in stringiness insofar as we know a string when we see it but also embedding stringiness in all sorts of different representations, as I have literally done in this email, so that we ourselves are judging to what extent the different representations represent the same thing. It's the difference between: imagining all the ways we can mess with a string which for us means with our eyes and fingers vs imagining what it would be like to be the string itself: and from the string's own perspective, it's the shortest path between A and B, as straight as an arrow: and it's we who are all in a tangle.

So I should say basically that the branch of mathematics that studies "analogical sequences" of this type, like:

Algebraic Symbols -> Wires/Boxes -> Matrices -> Entangled Quantum Systems across Space and Time

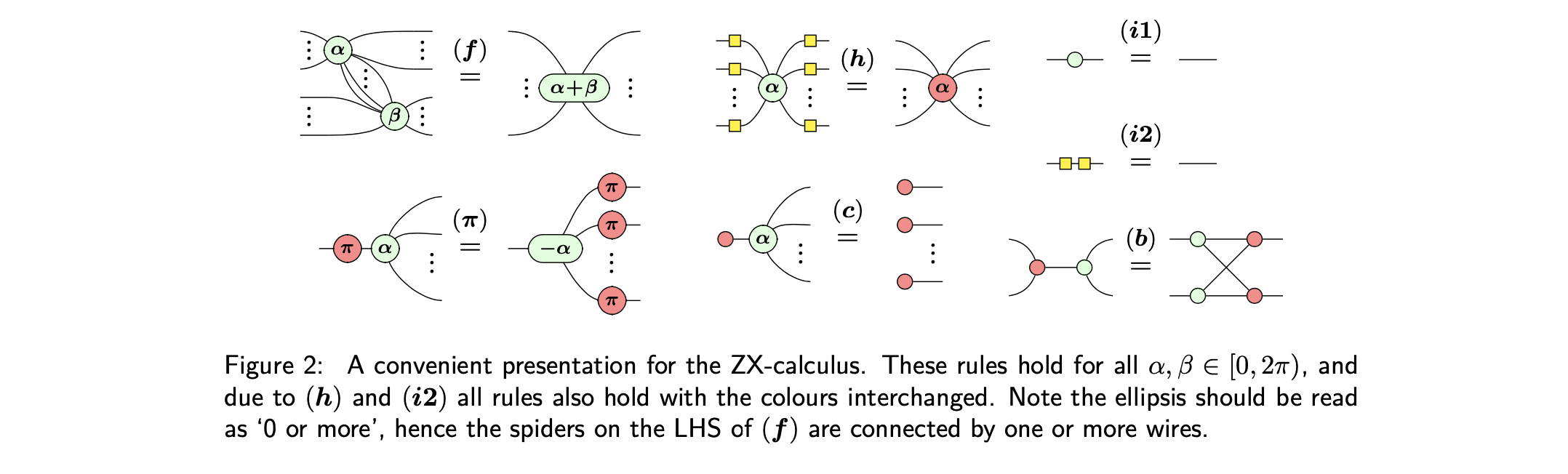

is called category theory. And in recent years, they've actually reformulated a huge portion of quantum mechanics in such a way that basically you don't even have to calculate a single number, multiply even the tiniest matrix: everything is expressed pictorially, in diagrams, using tactile and visual reasoning. No need for numbers (although you might want them in the end, and they're easily obtained). Just for flavor, the rules look like this kind of thing.

And I can attest that when thinking about this stuff, it's really convenient to be able picture these things in your head when reasoning about quantum problems, and seeing the answer is true as opposed to believing it.

And with regard to Coomaraswamy's world, maybe we'll see an eventual return to the pictorial reasoning of traditional art, souped up and overlaid with ideas ancient and modern, where the point is neither to resemble an original nor to innovate in purely aesthetic terms, but to communicate a precise meta(physical) meaning.

On the other hand, there is as much value in very abstract, general representations: for example, numerous useful symmetry groups have representations as matrices, so that we can represent them as subgroups of matrix groups. In other words, we can represent many different things with the same thing: matrices, and so easily perform transformations that break the original interpretation of the representation, expanding its scope.

One must use both.