History of Diagrams¶

People have been making diagrams since forever. In terms of our particular story, maybe things start with the Einstein summation convention. Feynman Diagrams. In the 60's, Penrose developed his graphical tensor notation. In the 80's, discoveries were made in the theory of knots and strings, whereby one can assign mathematical expressions to tangles, with tests sensitive to their knottedness, which is a topological property. Many people worked on this: from Louis Kauffman to Ed Witten. People were interested in it for many reasons, including those interested in topological quantum field theories, theories whose degrees of freedom are all global, because they didn't want to build in things like a spacetime metric at first. And in general people were thinking about quantum gravity and other things in increasingly "categorical ways."

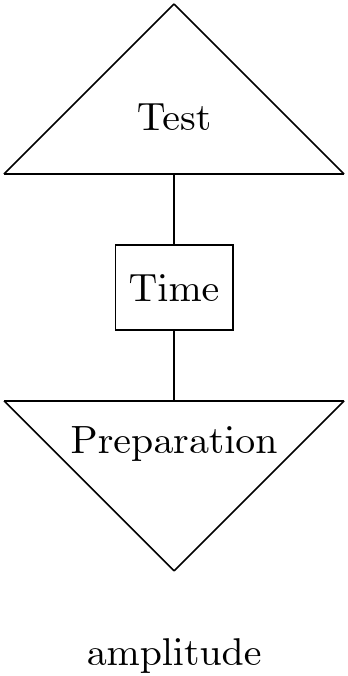

Anyway, to cut a long story short, in the early 2000's, Coecke and Abramsky start formalizing quantum mechanics in terms of the string diagrams, using category theory to prove the completeness of the diagram language for representing the theory. But I think overall it has to be understood in the context of an increasing interest in tensor network methods, whereby one tries to represent complicated quantum states in terms of simpler matrices that can be contracted together in certain patterns that is sufficient and simpler than representing the entire pure state in all its exponential glory. A closed tensor network is just a bunch of tensors with joined indices representing contractions, and in the quantum case, the full contraction gives the amplitude of the process. But one can rearrange the matrices quite a bit without changing the amplitude.

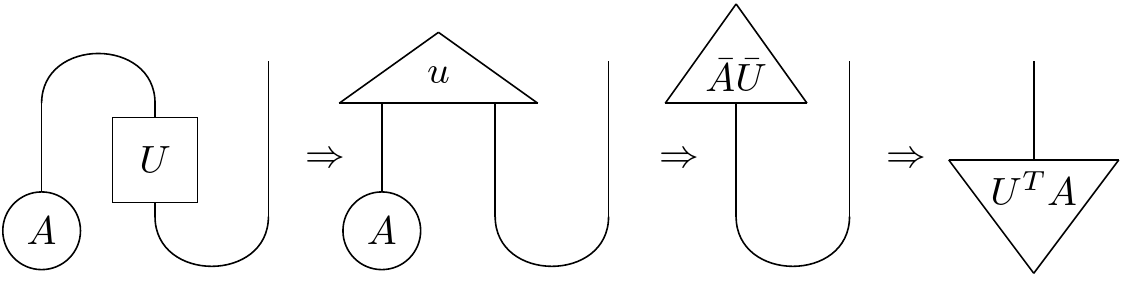

But indeed, the central insight of the Coecke/Abramsky diagrams is the identification of the cups and caps, so that one can factor out states into operators on wires, and view the wires as paths of quantum information flow. And all the ways one can yank and rearrange the elements of the diagram--they won't change the intrinsic quantum information flow: each equivalent diagram represents a different perspective on that one underlying unity.

Moreover, what it all reveals is how intrinsically two dimensional many of the central concepts are. Whereas algebra proceeds on a line, each character either to the left or right, on the plane things can be juxtaposed, and so many complicated algebraic identities become tautological or identical pictures. It doesn't even have to be spoken, because the diagram language itself doesn't make the unncessary distinction.

Pseudo Time Travel¶

So let's proceed to a somewhat literal interpretation of the yanking equation. After all, it's pretty crazy at first glance: the wires go up and over these caps and down around these cups, in other words, forward and backwards in time and across space!

But first, what do we mean by "backwards in time"?

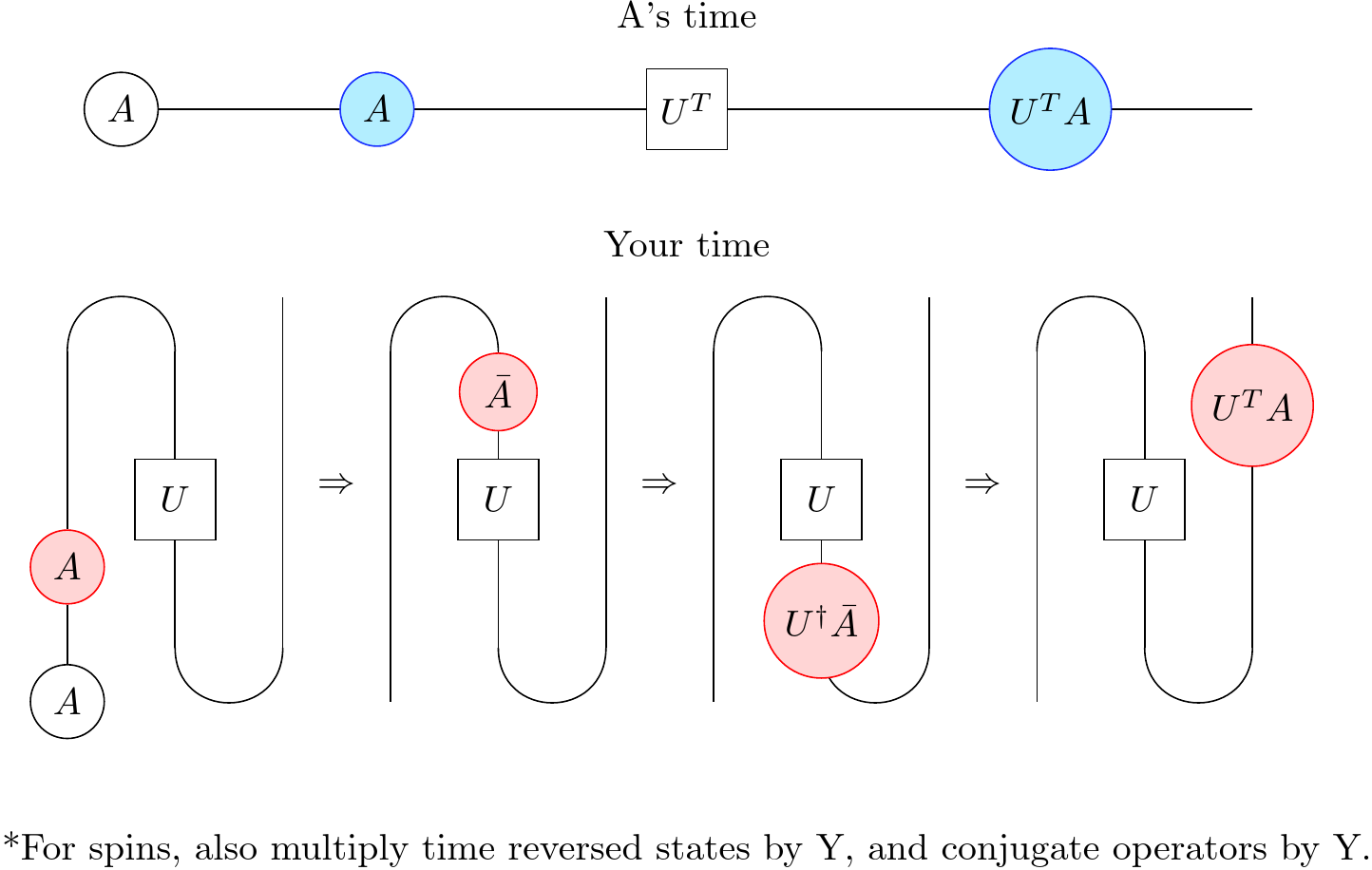

We take what you would see forward in time along that wire, and play the "video" in reverse.

Because obviously the particle doesn't move backwards in time in its own terms: it just proceeds along the wire, really, as if the wire were fully yanked. Indeed, from the particle's perspective, when you think the particle is going back in time, it symmetrically, would decide you were the one moving backwards in time. (Whereas we are free to yank and unyank diagrams as a matter of description, in real life, we have to imagine that if I yank a wire relative to me, then the rest of the diagram may get curled up to compensate. In other words, we can yank wires freely as a kind of gauge transformation. But in real life, if you yank, the whole world should unyank to compensate, no?)

I want to emphasize this fact about the diagrams, that you set them up, that there is an observer's perspective implicit in the construction. A cup is a state prepared across space at a certain time relative to you; a cap is a test you set up across space at a later time. Given them, you can calculate an amplitude and a probability that the preparation will pass the test.

It is you for whom going up in the diagram corresponds to time, you for whom going across the diagram corresponds to space. And given this set up, quantum information is forced to flow a certain way relative to you, in ways that counterintuively involve flow across space and backwards in time as well as forward in time, in order to satisfy the constraints you've set up (by your experiment, of course).

If there's time travel, however, I want to call it pseudo-time travel since it does not involve information transfer from the future, just as entanglement can lead to pseudo-telepathy, which leads to spacelike separated correlations, but not information transfer, since the correlations are related to irriducibly random choices of quantum outcomes. So you might say: okay, an operator goes up a wire, rounds a bend, and comes back in time along the middle wire. And I have an operator on that middle wire, and I say: ah but see at the first moment in time, the particle coming in from the future has already been transformed by the operator I have yet to apply: and so I could know about operator I'm about to apply before I choose to apply it! But this can't work. The mistake was in thinking that the cap at the top meant just one thing. Rather: you get a cap corresponding to a possible result of measurement. Like in the teleportation example, we measure in the Bell basis, and so that ends up being one of the four Bell states. If we're imagining a state going along the wire, it would encounter this cap zipped up as an operator. But there are four possibilities!

And we can't know which possibility we get until we actually make the measurement. So even if a particle flows backwards in time along the middle wire, and so comes back to us already transformed by an operator U we've yet to apply, it has also been transformed by the operator M corresponding to the measurement outcome: and we can't know which outcome we got! So we can't distinguish the influence of U from M, and so we can't necessarily get any information about our own choices/future outcomes from these states moving backwards in time. So: pseudo time travel. And yet, it seems like the simplest explanation for what happens.

So I want to say something like: even if the future is passing through here on its way out to some spatially distant destination, this future is encrypted to us. We only find out what the future meant when we make our measurements. We’re the ones who have organized time in this way, with our preparations, apparatuses, and measuring devices. The future is already here, on its way across space, and must always return home (to the future): we only recognize it as foreshadowed in retrospect.

Incidentally, you might wonder: what if when the state is moving horizontally across a cap or cup? Could we put an operator along the wire there, etc? As far as I can see, the answer is not really. From the state's own perspective, it's just going along a straight wire the whole time. You're the one who sees it "as a cap" as a spatially distributed "outcome." So if you wanted to imagine the state of A when it is actually "in the cap", you could imagine contracting it with the cap, etc.

Would you rather be teleported or wormholed?¶

The second answer seems obvious. After all, the wormhole is like an open portal you walk through, it seems more geometrically continuous than the teleportation case, where someone extracts classical data from you, destroying you in the process, transmitting the data via satellite, etc. And yet, it seems like these diagrams suggest there isn't really any difference. If you follow the line in the diagram, "you" would just "bounce" off the measurement, not be destroyed, and use the entanglement with the "portal" to slide across space, and then go backwards in time as the portal, slide across space via the portal's original entanglement with its twin, and then go up forward in time as the twin, to when and where the correction is applied. So who's brave enough to try?

Incidentally, one could wonder whether it's plausible at all that things like teleportation and wormholes could exist, given that we don't see any obvious evidence of them in the macrocosmic world around us. But it's less strange than at first glance. It just turns out there's two ways to get from A to B, "locomotion" as we normally think of it, and teleportation, but each come with a cost. Just we have to to burn up ATP, swing our limbs around etc, in the latter case, we need to prep entanglement at the source and destination, and set up a phone line between them. For us big humans, naturally the former way is so obvious that the possibility of a second option didn't occur to us, but for subatomic particles, the second way is perhaps more natural and convenient, and in fact, it may be that what we normally think of as locomotion is just tiny little bursts of "teleportation" at a microlevel--or at least, that wouldn't be a crazy way to think of it: a classicalish spacetime woven out of wormholes.

Non-maximally entangled cups and further generalizations¶

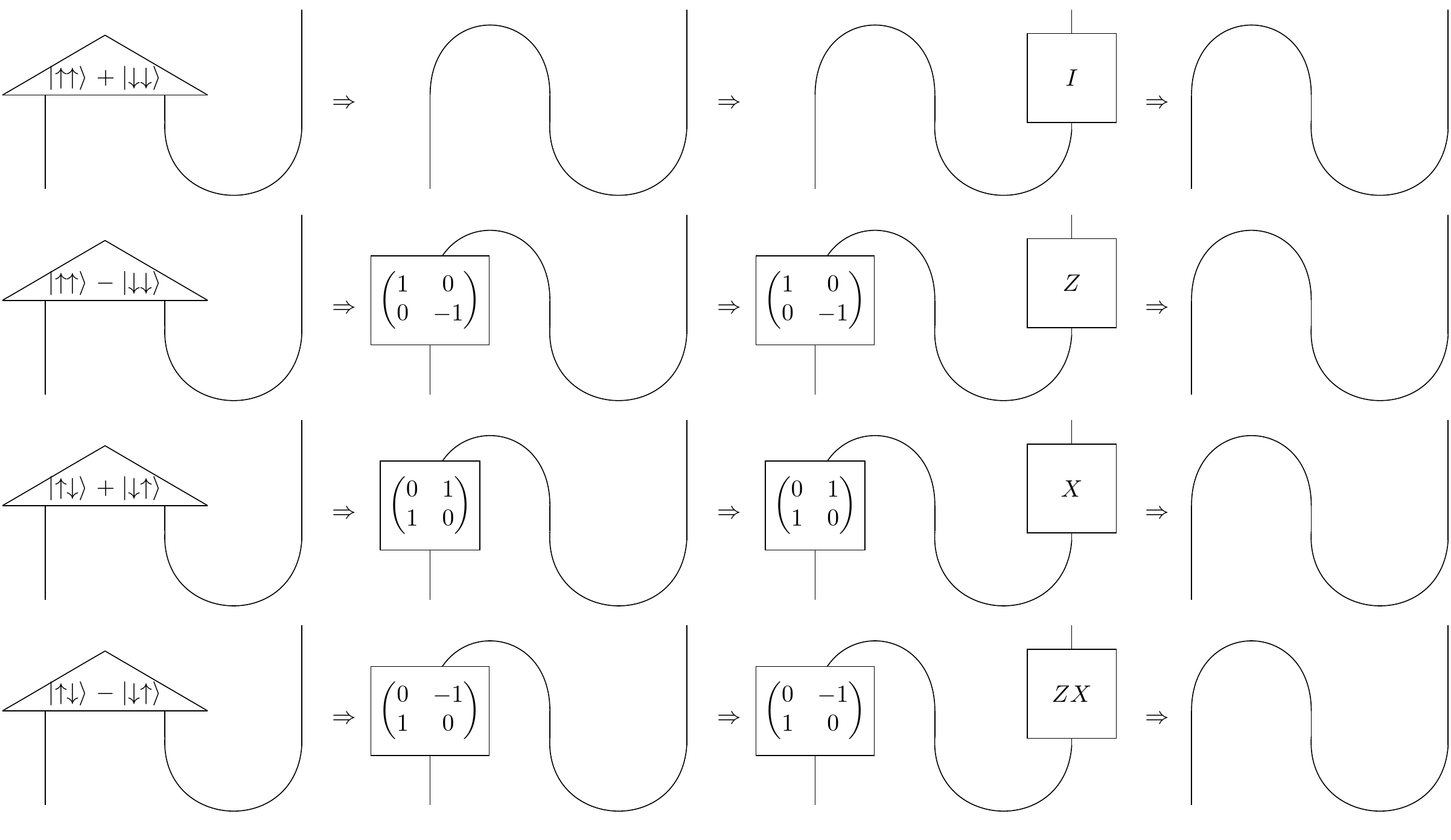

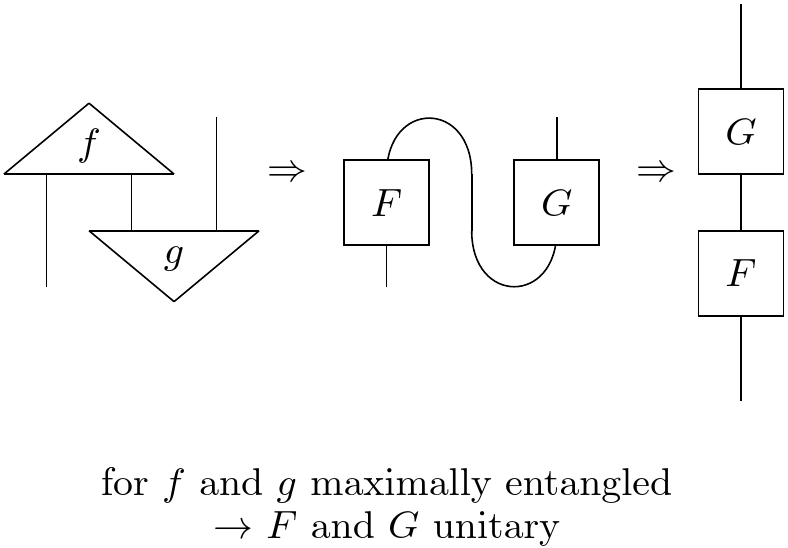

So far we've considered maximally entangled cups and caps, like the Bell states. We find:

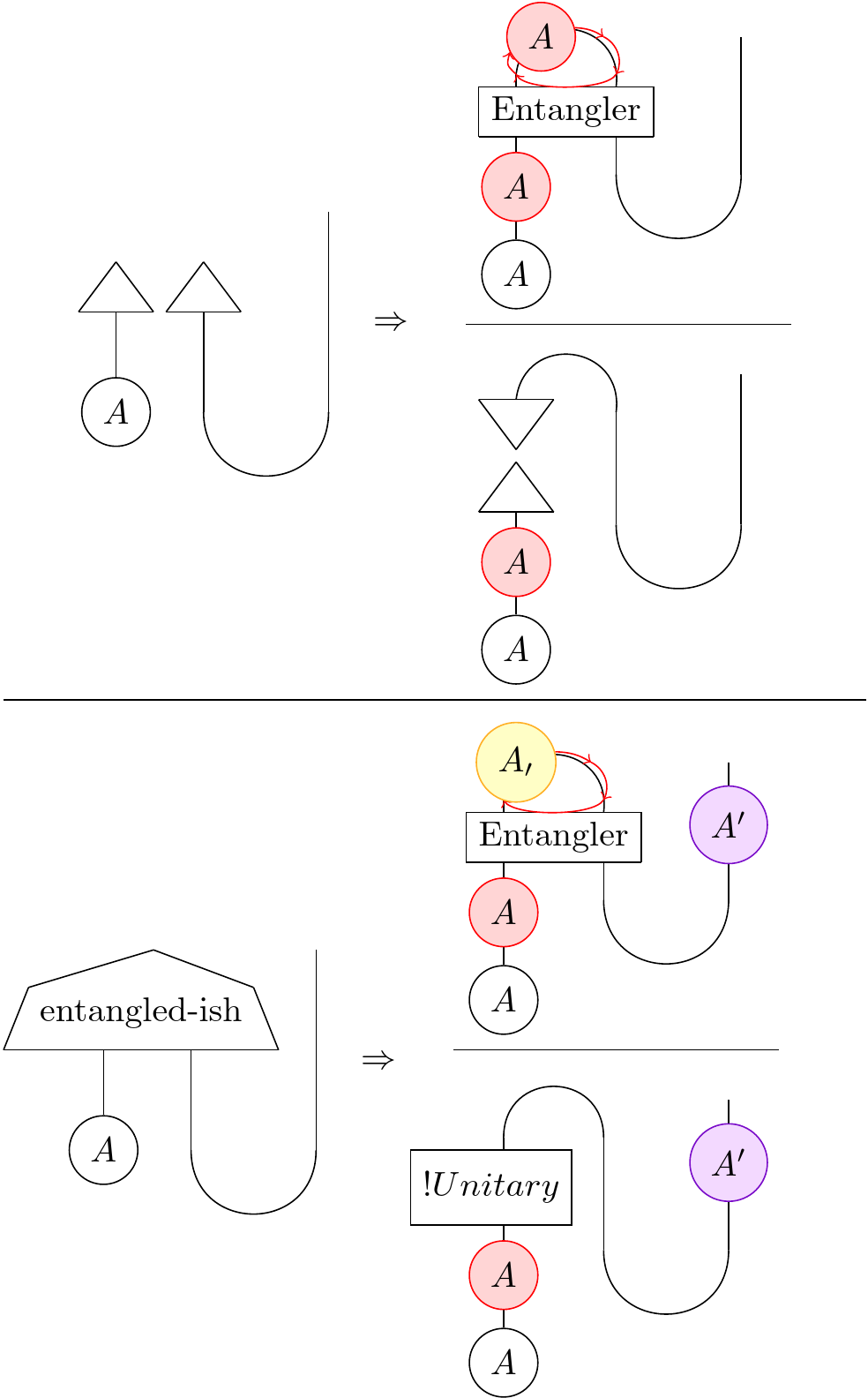

But what about non-maximally entangled, or even separable states? If we imagine quantum states as moving along wires, wouldn't this represent a kind of interruption in the line?

We can actually think of it in two ways. We could still do our trick and zlurp out an operator from a cap, but this operator would then have to be not unitary. And so it can block the state entirely, or just let part of it through. Alternatively, we could repace a separable/non-maximally entangled cap with a normal cap, but first apply an entangling gate. It's simply a basis shift: instead of doing a separable test on a possibly separable state, we do an entangled test on a possibly entangled state. So that if the right separable state approached the test, the entangler would precisely give the normal cap state, so it passes. In that case, we could imagine one part of A gets through, while another part of A gets trapped in a closed time-like curve between the entangler and the cap.

How do we feel about that?

On the one hand, it's not that weird to make a closed time-like curve per se: you can read any closed diagram as such! And such a closed diagram reduces down to a scalar, an amplitude. On the other hand, if we read this as a history, we feel kinda bad for the little guy trapped up there.

In principle, however, there could be higher order transformations: in other words, on the tensor network itself as a whole, in which case, the little guys in the loops could be liberated... We shall see some ideas in that direction in the SYK section. And I also want to say if you don't feel bad for those guys, you don't really believe in the Many Worlds theory in a way that has real consequences.

Finally, we can imagine all sorts of generalizations of cups and caps for multiqubit states, and analyze the kinds of wires relative to operators we can draw, and tensor network methods play an invaluable role.

Also:¶

Also, we could wonder some more about higher order transformations between diagrams. Relationships between diagrams. Maybe for me, your wire isn't the identity, but fattened into some matrix. Maybe for me one separable state, for you is a pair of entangled states. We're used to ideas of perspective in terms of the Poincare group: rotations, translations in space/time, boosts, where everyone agrees on the nature of the vacuum and the particles that can fill it. But when we consider more general perspective transformations (as in a curved spacetime or an accelerated reference frame), we can have more radical shifts in how one POV can be built out of another.

About Black Holes¶

So shortly after Einstein finished General Relativity, various simple solutions were found, for example, the Schwarzchild black hole solution. But apparently, quantum field theory stole all the limelight from the 30's to the 60's, when finally GR had a revival and John Wheeler coined the term black hole for an "object" which is so small and yet so massive that it's gravitational pull is so strong that not even light can escape its pull. The big question was what happens to stuff that falls inside a black hole? After all, quantum mechanics is taken to be a unitary theory overall: since probabilities must be preserved, something can't just dissapear can it? People starting thinking about what you would see if you watched someone fall into a black hole. You'd see them getting ever closer, ever more slowly (due to time dilation), to the so-called event horizon, the point beyond which things are blank because all the light is trapped inside and so can't escape. They'd get red shifted and so seemingly smeared out over the surface of the black hole before fading out. This was mainly from classical considerations. By the equivalence principle, just the same, however, from the frame of reference of the person who falls in, they would describe this as just sailing right through the event horizon (perhaps not even realizing it's there) and then they continue accelerating right on until...

It was in the 70's that Hawking and others started treating black holes in a quantum way. He imagined pair production of entangled particles right on the event horizon that takes a little energy from the black hole. One particle happens to be inside and so can't escape, but the other flies off, and the black hole gets a little smaller. Eventually the black hole would evaporate, and all that would be left is the so called Hawking radiation. So black holes have a temperature. Another part of the story is that it was conjectured by Bekenstein and Hawking that the entropy of a black hole is proportional to its surface area, not its volume as you'd might think: as if all the degrees of freedom of the black hole were on its surface.

By the 90's, a certain philosophy was developing: black hole complementarity. It said: okay, we're outside the black hole, and we need to assign some quantum state to the black hole. But we don't know what happens to what falls in. But what do we have? Well, we have the quantum state on the event horizon itself and we have the Hawking radiation. Let's conjecture that in some sense: the event horizon + Hawking radiation = black hole interior. That there's a kind of perspective switch going on, a change in vacuum state--we'll return to this idea after we've gone through the SYK model. And what an observer who falls into the black hole would experience as the interior geometry and matter, we experience as the event horizon + Hawking radiation.

What one observer experiences as sailing through empty space, the other observer sees as someone getting "scrambled" over the surface of a black hole: so that one becomes encoded "holographically" on the surface, and later emitted as Hawking radiation.

Concrete examples to this effect were produced, eventually leading to the Ads/CFT proof in a certain context by Maldacena in the late 90's. On the one hand, one had a conformal field theory (in other words, a scale invariant one) defined on a spatial boundary which was mathematically dual to an anti-De Sitter geometry, a gravitational theory in one dimension higher. The idea is that as things spread across the boundary, they enter deeper into the interior emergent geometry, the bulk. So that there is an intimate relationship between depth and scale. This has been modeled in many other forms, in terms of tensor networks, error correcting codes, and much effort goes into making very precise the so-called "holographic dictionary." And the significance of the SYK model is that in the limit it can be shown to approximate a conformal field theory with the right properties for a black hole: fast scrambling, etc. Not a particularly realistic 3+1d black hole with all the dressing, but let's leave that to the experts.

Now one can imagine the following scenario: put a Dyson sphere around a black hole and carefully collect up all the Hawking radiation for a certain sufficient amount of time (cf. Page curve), and then take that radiation compress it into a black hole! Since the radiation had to be maximally entangled with the original black hole, now you have two entangled black holes, and can do your wormhole experiment. So even a "one sided" black hole actually has two sides: but you can think of the second side being the Hawking radiation: and in fact, maybe you can imagine there's little wormholes leading from the Hawking radiation back home.

And so, most recently, it was discovered that entangled black holes can be rendered traversible by the right external coupling. And you can imgine many variations on this theme: three mouthed wormholes, etc, with all the intricate structure of entangled states. For example, there are entangled states of 3 systems in which each one is entangled with the other two together, but neither of the two individually: and then one has to imagine all sorts of interesting geometric stuff happening in the interior.

And many people wonder about the generalization of these ideas to general horizons.

Identifying the Observer¶

Just wanted to make a general philosophical clarification regarding some of the language above.

I think at present it's most fair to say that when we talk about observers in physics we're not necessarily talking about someone's conscious experience. When we say things like "from this observer's perspective", etc, we're talking what it is maximally possible to know from a given point of view: not whether one actually knows it! We're representing what it is possible for one to know in a given situation, from a given perspecive. Whether you take advantage of what's there, when you're there, is another story.

And yet, I think there does remain a mystery still. Which is that we of course ourselves are part of the physical situation. If we don't know all that it is maximally possible to know, then why do we know what we do know?

It's not entirely crazy to think that the underlying physics of our body could be interpreted as our “unconscious background”, the invisible space of possibilities against which definite occurrences “make sense” for us. That’s at least possible.

Another thought is that: in the diagrams, we have this natural duality between unitary operators (a step in time) and maximally entangled states (a step across space). This sort of "time/space interchange" seems bizarre at first, and yet we are everyday confronted by the bizarre conjuction of two facts: a) I experience time flowing forward as myself b) I am somehow distributed across my body in space. The point of science is to eventually make this actually not seem paradoxical at all. (But of course, we love it because of the paradox.)